Cruelty at its peak

‘Conflict of elephants with human beings in and around Amchang Wildlife Sanctuary on the outskirts of Guwahati in Assam is a common phenomenon almost all the seasons.

In Narengi Army Station also, often the herds of wild elephants keep moving in different units of the military station, as the entire area is part of elephant habitat.

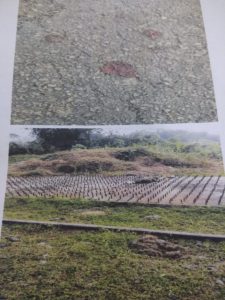

December 25, last year, at about 2 am one wild elephant was injured at supply depot of Narengi Army Cantonment, after getting speared into feet by iron spikes driven into the ground at supply depot by Army personnel.

This type of cruel effort to keep the elephant at bay is definitely going to defeat the very spirit of wildlife protection and empathy for wildlife. Less harmful is the way to raise solar electric fencing around depot.’

This was part of a letter written by the Divisional Forest Officer, Guwahati Wildlife Division on December, 27 last year to the Colonel, Adm Comdt, of Station Cell, Narengi Army Station Guwahati after the death of elephants due to severe septicemia attributed to the iron spikes.

While the first case of death was detected on December 25 last, the recent case was detected in February when the wild jumbo carrying the wound for long died without responding to treatment.

The Army authorities put the spiked barrier to secure its supply depot almost adjacent to the Amchang Wildlife Sanctuary, in the Kamrup district of Assam.

The Sanctuary has a population of more than 50 elephants and herds of the wild pachyderms would frequent the cantonment, once part of their traditional habitat. The movement of the pachyderms was obstructed after a huge wall came up as protection to the golf course adjacent to the forest.

On January 11, the brutally severed body of a woman, Maina Kalita who hails from nearby Jorabat, was recovered from the forest adjacent to the Narengi Cantonment. The woman was supposedly killed by wild pachyderm.

Elephants have sharp memories and frequent their traditional routes and habitats now being inhabited by humans. These giant species that require hundreds of kilograms of food each day are also forced to find food where it exists like croplands, gardens, kitchens and so on.

There may be more such cases.

“There may be more cases of elephant deaths due to the spiked barrier,” said Pradipta Baruah, divisional forest officer, Guwahati Wildlife Division. In fact the barrier has led to severe injuries in a number of elephants. We recently treated one with severe wounds,” he said.

The iron-spiked barrier that proved to be death trap for jumbos invited sharp reactions from conservationists throughout the State. Kaziranga Wildlife Society, Early Birds, Green Guard Nature Organization along with a number of other nature organizations of the State condemned the ‘insensitiveness’ of the authorities concerned and demanded immediate removal of the spiked barrier before it causes any more harm.

Several hundred elephants have been killed in Assam in the last decade. While scores have died after being hit by running trains, others fell to electrocution, bullet wounds, poisoning, starvation and there are also reports of death of elephants from septicemia as result of wounds from sharp bladed fences in and around cultivations particularly tea plantations.

Fear and insecurity leads to the dipping of tolerance level in both humans and elephants. To avoid injury when actually elephants are destroying homes or laying waste the stores is no child’s play.

Retaliatory killing is on the rise that reflects that human-elephant conflict mitigation approaches never reached the targeted level.

Asian elephant numbers show declining trend.

Official sources reveal unnatural deaths of around 68 wild elephants in 2018. However, unofficial sources claim the state lost more than a hundred pachyderms that also include mothers and calves (death of baby elephants falling into tea garden trenches are sometimes not included in official reports).

Asian elephant numbers decreased to half of what it was in the last century in their last bastions in India, Sri Lanka and Bhutan.

As per the elephant census in 2017, India is home to 27,312 elephants, accounting for 55 per cent of total world elephant population.

Northeast India used to be home to over 10,000 wild elephants. That is 25 per cent of the world’s elephant population. More than half of the elephant habitats in the north-eastern region have been lost since 1950, stated a WWF-India official working for elephant conservation in the region.

Assam is home to nearly 6,000 wild elephants.

Elephants share a crucial relationship with forests that has evolved over millions of years. When forests fragment, the pachyderm’s populations fragment too. With fragmented forests, elephant populations across all its once strong holds in the continent are now doomed to dwindle.

Rapid deforestation and fragmentation has resulted in isolated elephant populations with very limited resources.

What would normally serve as food for elephants is now utilized by humans; large stretches of elephants’ habitat are cleared for agricultural and other developmental activities and much of their migratory pathways are also taken over leading to confrontations and conflict between man and animal.

About 500 humans lose their lives due to human-elephant conflict in India annually, and around 100 elephants are killed in retaliation for the damage they cause to human life and property.

More than 1000 people have fallen victim to wild elephants in the last decade in Assam.

Government, semi-government projects in important elephant corridors.

Man-animal conflict is a result of rampant destruction of forests. Animals stray into human habitations in search of food and space. We are trying to save forests by making them encroachment free – is the usual refrain that comes from those at the helm of affairs.

In reality, encroachment on even critical wildlife habitats continued under the nose of the competent authorities. In fact clearing of protected areas for government projects – has made human-animal conflict turn into a desperate crisis.

Clearing of forests and destruction of the elephant corridors for small tea gardens, hotels, resorts and other developmental activities in the Assam-Bhutan-Arunachal border are drivers of human-elephant conflict manifesting in crop-raiding, damage to property and loss of human and elephant lives.

Clearing of forests in inter-state and international boundaries added to the worsening situation. Illegal stone mining in the Kaziranga-Karbi Anglong-Intanki landscape and Dhansiri-Lungding are major drivers of elephant depredation in the two major elephant reserves in the State.

More than 20 districts of the State bore the brunt of human-elephant conflict. Sonitpur is one of the worst hit.

An Army firing range set up inside the Sonai Rupai Wildlife Sanctuary in Sonitpur district; construction of a high wall for a government-supported bamboo project in Karbi Anglong on the Assam-Nagaland border (part of an elephant reserve); Indian Oil Corporation Ltd’s oil dispatch terminal in the Golai elephant corridor; dumping of municipal waste in the Dehing-Patkai Wildlife sanctuary (elephant reserve); a two-kilometre stretch of a wall built by Numoligarh Refinery Limited inside elephant corridor in Telgaram area in an area marked by the environment ministry as ‘No Development Zone’ are examples of projects cleared by the government at different times flouting all norms of the 1972 Wildlife Act.

It becomes absolutely necessary that Compensatory Afforestation Fund collected from the proponents of development projects that destroy or fragment forests should be used to consolidate the country’s wildlife habitats. This would have a huge impact from a wildlife, biodiversity conservation and watershed perspective.

Despite the fact that elephants remain an integral part of our culture, heritage and religion they continue to remain neglected. Conservation strategies and conflict mitigation approaches largely remain confined to policy documents and boardroom discussions.

At a time when habitat loss and human-wildlife conflict are becoming increasingly commonplace in the country, what we need is governmental intervention and a holistic approach across government and private lands to protect and manage natural ecosystems and ensure connectivity between the remaining wild habitats in a fragmented landscape.

Mubina Akhtar is an environmental journalist and wildlife activist. She can be reached at: newildflowers@gmail.com