The Woman Who Redefined Pleasure for Women

Written by: Kalpana Pandey

Born in 1929 in Wichita, Betty Dodson grew up in an era when open discussion of sex was virtually taboo. Raised in a conservative household, she learned early on that questions about desire and self-pleasure were met with silence or admonishment. Growing up in Wichita, Kansas, she developed an early passion for drawing and painting. By the age of 18, she was already contributing to her family’s income as a fashion illustrator.

After moving to New York in 1950, Dodson studied at the Art Students League of New York under renowned painter Frank J. Reilly, honing her skills in figure drawing. Artistic endeavors marked Dodson’s early years in New York—she exhibited erotic art in galleries and honed her skills as a painter. Her erotic art, though marginalized, blended classical techniques with bold depictions of female sexuality. As she immersed herself in the city’s creative and countercultural scenes, she also began to question the rigid expectations imposed on women. She exhibited erotic art—works that boldly celebrated the human body at a time when such imagery was largely censored. Her artistic vision later intertwined with her sex education, as she used creative expression to explore and celebrate female anatomy and sexuality.

She married an advertising executive but divorced due to sexual incompatibility. Divorce carried significant social stigma in mid-20th-century America, particularly for women. Dodson’s career as an artist specializing in erotic themes clashed with the male-dominated art world of the 1960s–70s, which dismissed her work as unserious or pornographic. Her representational style also fell out of step with abstract trends, limiting her recognition.

After her art career faltered, she worked as a freelance lingerie illustrator, a job she found creatively unfulfilling but necessary for survival. Beyond lingerie ads, she illustrated children’s books and worked for Esquire and Playboy in the 1960s, though she later critiqued the latter for its male-centric objectification of women. After a painful divorce in the mid-1960s, she embarked on a journey of “sexual self-discovery,” a quest to understand and reclaim the pleasures that had long been denied or hidden away. Dodson’s shift from a sexless, conventional marriage to a life devoted to self-discovery is a less-discussed but pivotal part of her story. Her personal experiences of sexual repression and societal judgment sowed the seeds for what would become a lifetime commitment to sexual liberation.

Betty Dodson’s personal struggles eventually inspired her to create BodySex—a series of workshops that redefined how women perceive and experience their sexuality. In workshops, Dodson used storytelling to help women reframe sexual shame. These sessions provided a safe, non-judgmental space for women to explore their bodies and embrace orgasm without shame. Dodson’s innovative approach integrated clitoral stimulation (often using the Hitachi Magic Wand), a “resting” metal dildo for vaginal penetration, conscious breathing, and pelvic movement, all designed to foster self-pleasure. Scientific studies have validated this method, with research showing that 93% of previously anorgasmic women achieved orgasm using her technique. By teaching women to love and understand their bodies, Dodson empowered them to resist and challenge the societal forces that seek to control female sexuality.

For many women, the message was clear from childhood—touching oneself was something to be hidden and even condemned. Dodson recognized that this internalized shame was one of the greatest barriers to sexual liberation. By confronting her own past and embracing her desires fully, she set an example for countless others. Her workshops were not just about learning techniques; they were about dismantling a lifetime of self-repression and reclaiming a sense of dignity and agency.

Her candid discussions about the emotional and psychological benefits of self-pleasure resonated with a generation of women who had long felt alienated by traditional sex education. Dodson argued that masturbation was not a solitary, shameful act but a natural and empowering form of self-care. Through her teaching, she encouraged women to see their bodies as sources of pleasure and power, rather than as objects to be controlled by external forces. Beyond the external battles with patriarchal institutions and societal taboos, Dodson’s journey was also a deeply personal one—a fight against the internalized shame that many women carry as a result of years of cultural repression. In interviews, she often recounted her own struggles with guilt and self-doubt, particularly in the early years of her sexual awakening.

In a society where female sexuality was tightly regulated and shrouded in guilt, her public discussions about masturbation, orgasms, and self-love were seen as both radical and dangerous. Mainstream America, steeped in patriarchal values, had long dictated that sex was something to be experienced only within the confines of marriage and exclusively for procreation. Anything that deviated from that narrow framework was automatically suspect. Within feminist circles, Dodson’s workshops sometimes provoked controversy. Some critics argued that her methods were too explicit or that her focus on self-pleasure detracted from other political priorities.

When she first began hosting BodySex workshops in the early 1970s, many were skeptical—even within feminist communities. Critics questioned whether the public display of masturbation and explicit discussions of erotic pleasure could ever be reconciled with feminist political ideals. The reaction was mixed: while some hailed her as a liberator, others dismissed her work as frivolous or too radical for polite society. While Dodson aligned with feminism, her focus on sexual pleasure and workshops involving vibrators clashed with factions of the movement that viewed pornography and explicit sexual content as exploitative. At a 1973 National Organization for Women (NOW) conference, her vulva slideshow was met with hissing, though her vibrator demonstrations gained traction. Mainstream society condemned her work as immoral. Promoting masturbation—a taboo topic—challenged norms that tied female sexuality to marriage and reproduction.

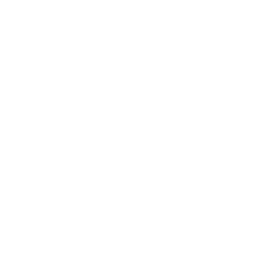

Her first book, Liberating Masturbation (1973), was rejected by mainstream publishers, forcing her to self-publish. Even when Sex for One (1987) became a bestseller, its content faced censorship and dismissal as “niche” or “indecent.” Her EEG study on masturbation’s meditative effects, conducted on herself, was marginalized by a medical establishment that historically ignored women’s sexual health. Workshops and explicit content risked legal challenges in an era of obscenity laws. Her reliance on grassroots promotion (e.g., workshops, direct sales) reflected a lack of institutional support.

Though her work aimed to include disabled women, broader societal neglect of marginalized groups’ sexuality limited its reach. As a white woman, she navigated privilege but still confronted systemic sexism. Dodson funded her activism through book sales and workshops, facing financial instability. Dodson’s struggle was not confined to cultural backlash alone. Throughout her career, she also found herself at odds with institutional forces that sought to censor or marginalize her work. From the conservatism of mainstream media to the restrictive policies in educational settings, Dodson’s efforts to teach women about their bodies were met with bureaucratic hurdles and, at times, outright hostility. In the 1980s, her mail-order vibrator sales drew scrutiny from postal authorities. She circumvented bans by labeling devices as “massagers” and including educational pamphlets to frame them as health tools. When her erotic art was confiscated by customs during international exhibitions, she worked with the ACLU to argue for artistic expression rights.

Yet Dodson remained resolute, arguing that understanding one’s own body was not merely a personal act but a political statement against the control and repression imposed by patriarchal norms. Her famous dictum—“Better orgasms, better world”—became a rallying cry for those who believed that sexual liberation was inextricably linked with overall personal and social emancipation. For Dodson, every act of self-pleasure was an act of defiance; every time a woman discovered the fullness of her own desire, she chipped away at the structures of domination that had kept women silent and subjugated for generations. One of the more endearing, yet less documented aspects of Dodson’s persona was her use of humor. Whether it was introducing her own body as a “best friend” during workshops or playfully critiquing mainstream feminist texts, her irreverent wit helped break down deeply entrenched sexual shame. This humor made her teachings more accessible and helped women feel less isolated in their struggles with sexual repression.

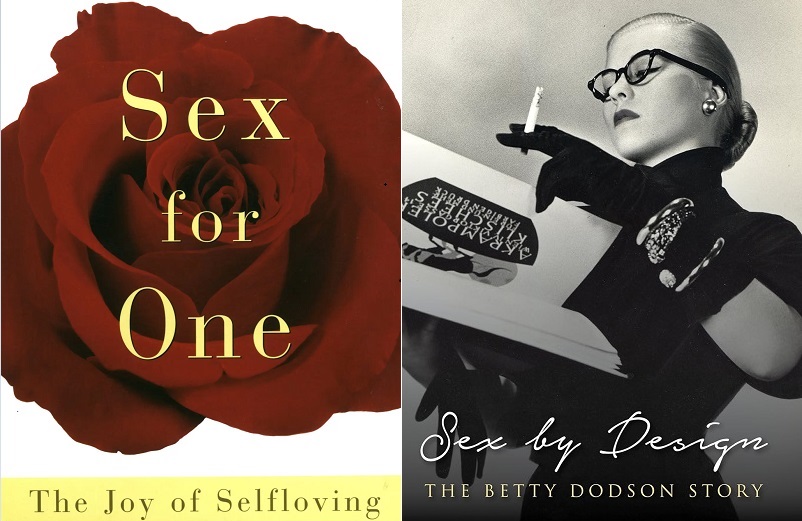

Yet Dodson pressed on. She documented her methods in books such as Liberating Masturbation: A Meditation on Self-Love and Sex for One: The Joy of Selfloving, which went on to become international bestsellers, translated into dozens of languages. Dodson authored several memoirs—such as My Romantic Love Wars and Sex by Design—which offer an intimate look at her personal struggles, her artistic evolution, and her relentless commitment to sexual liberation. These publications not only demystified the act of masturbation but also provided a tangible roadmap for women to break free from decades of repressive sexual education. In doing so, Dodson effectively redefined what it meant to be a sexually autonomous woman in a society dominated by male-centric narratives.

Dodson was known for her frank, often humorous critiques of both traditional and mainstream feminist approaches. She famously criticized works like Eve Ensler’s “The Vagina Monologues,” arguing that they sometimes reduced female sexuality to a narrow, anti-male perspective. Dodson believed in embracing a fuller spectrum of sexual experience, free from political manipulation or simplistic moral judgments.

Her candid discussions about the emotional and psychological benefits of self-pleasure resonated with a generation of women who had long felt alienated by traditional sex education. Dodson argued that masturbation was not a solitary, shameful act but a natural and empowering form of self-care. Through her teaching, she encouraged women to see their bodies as sources of pleasure and power, rather than as objects to be controlled by external forces. Her insistence that masturbation is a form of self-love and